As theatre districts around the world continue to recover from the pandemic that brought the industry to a halt, should New York look to London — or even its own past — for guidance?

Before the broadcast of this year’s Olivier Awards — London theatre’s version of New York’s Tonys — on April 2, 2023, Society of London Theatre President Elanor Lloyd spoke to the audience about live theatre’s ability to provide “empathy intervention,” citing a recent study. Indeed, empathy appeared to be a recurring motif for the night. The stage adaptation of Hayao Miyazaki’s 1988 feel-good animated classic, “My Neighbor Totoro,” secured six out of nine nominations, the most out of any production that night. The show’s puppet master and nominee for best choreography, Basil Twist, described puppetry, used to a great extent in the production, as “the essence of theatre; it’s the imagination; it’s empathy.“

Yet, across the pond in New York, the mood among the theatre community was somber enough to match London’s grey skies. New York City’s longest-running show, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “The Phantom of the Opera,” was wrapping up its last performances and closed for good on April 16, 2023. It ran for 35 years.

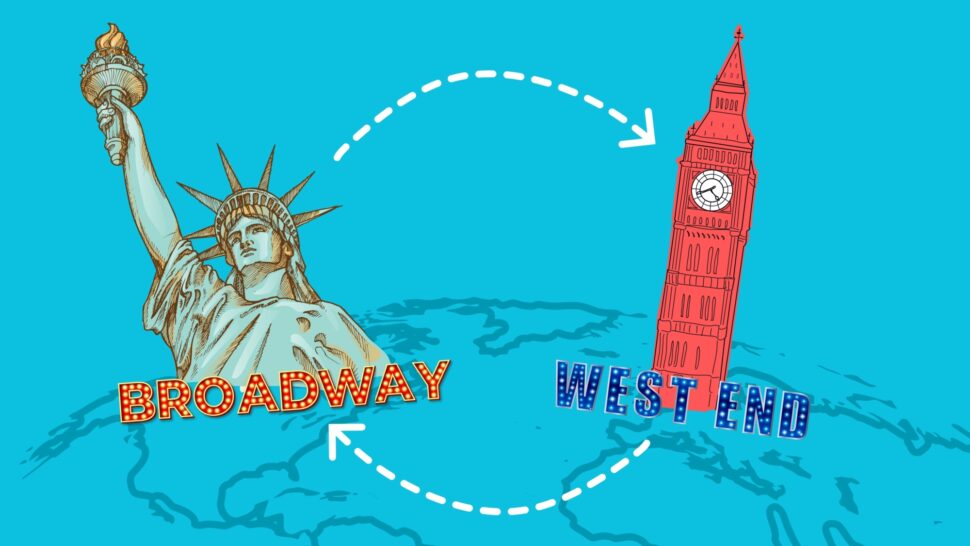

Despite having its origins in London’s theatre district, the West End (where it’s still running), “Phantom” shaped an identity of its own in the US. The titular character’s mask is almost as synonymous with the Statue of Liberty as a symbol for New York City.

If you were to ask a random New Yorker a few years ago if they believed “Phantom” would ever close its doors… They would have laughed in your face and probably said that a gorilla climbing the Empire State Building, ala “King Kong,” was more likely.

With the advent of “Phantom” coming to a close, publications ran story, after story, after story, reminiscing the musical’s impact and legacy. You’d almost think you stumbled on the obituary section by accident.

With this recent focus on New York’s theatre district, Broadway, comes a time of reflection. It’s no doubt that a mix of the pandemic, inflation, declining ticket sales, and the high costs of the show’s production slew this phantasmic musical beast. “Phantom” was, first and foremost, a commercial musical. The main goal was always to generate profit and run it like a business.

Those unaware or new to live theatre might believe that every show operates this way. However, there also exists the world of “subsidized theatre.” These shows are financed by the government, something the West End has in spades, despite recent efforts to cut funding. In fact, the “My Neighbor Totoro”adaptation was produced primarily by the Royal Shakespeare Company, which receives the second highest annual funding from the UK government.

Perhaps as part of New York City’s attempt to revitalize itself with its “We ❤️ NYC” campaign, the city should consider diving into the realm of subsidized theatre. It would certainly take attention away from its controversial logo.

Of course, many Americans (especially policymakers) would gawk at the idea of the government funding the arts, especially during today’s economy struggling to recover from both the pandemic and inflation.

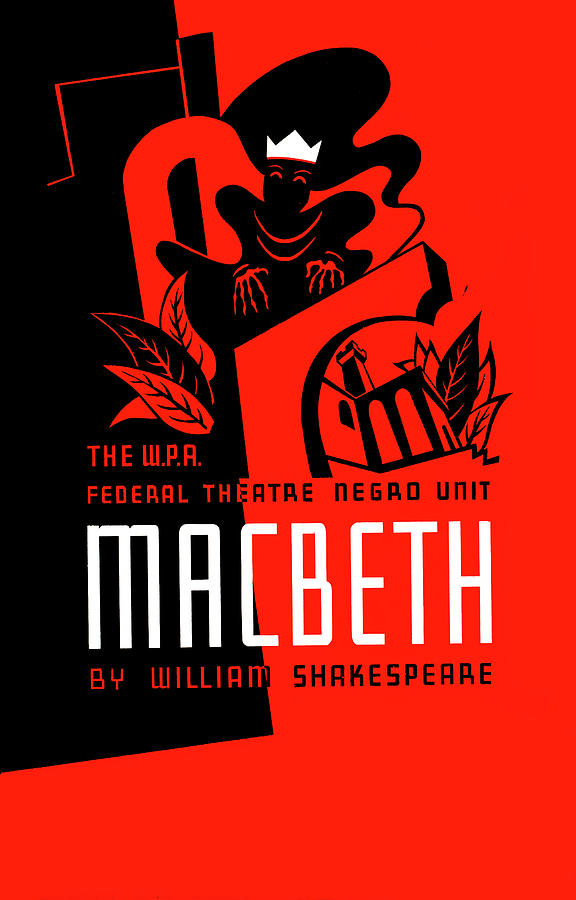

Yet, there is historical precedent to this kind of proposal. In 1935, part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program included the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Theatre Project. The program marked the first instance of theatre being supported by the US government. Up to 10,000 jobs were created, with around 1,000 productions made in 40 states. Not only did the Federal Theatre Project allow for the arts to be accessible to millions of Americans, but it also gave the spotlight to novice playwrights and Black theatre.

Household names in American theatre and cinema like Elmer Rice (Director of “The Adding Machine” and “Street Scene”) and Orson Wells (Director of “Citizen Kane”) made their debuts thanks to the project. The latter even adapted an all-Black version of Macbeth with a Caribbean setting via the program. Sadly, the project lasted only four years and was terminated by Congress after the McCarthyite House Un-American Activities Committee investigated and accused productions of harboring leftist and communist ideals.

It is about time for the NYC government to consider funding a new, modern, “Theatre Project” for Broadway. Legendary American playwright Arthur Miller (Writer of “Death of a Salesman” and “The Crucible”) once made a similar argument in an op-ed for the New York Times in 1947.

While programs like the Theatre Development Fund (TDF) exist to cheapen Broadway tickets, certain venues like the Lincoln Center and Manhattan Theater Club also operate as non-profits. Yet, due to their nature as non-profits, they still need to recoup their operational costs. TDF’s most prominent venture, TKTS booths, has just two in-person locations within the busy Manhattan borough. Keep in mind this is a city with a population of millions. And many of those “discounted tickets” still have starting prices of over $100.

Meanwhile, you could watch three or even five shows in London for that price. It’s a wholly inaccessible system that (literally) robs and restricts New Yorkers from only seeing a few shows a year. But, of course, that’s if they could even afford tickets with the already high costs of living in the city.

Navigating convoluted systems to save only a few bucks on tickets simply doesn’t work, especially if you’re making a spontaneous trip to the Big Apple and want to catch a show at the last minute. A far more efficient solution would be for the city government to fund new productions and make live theatre accessible for all budgets.

Not only would subsidizing shows allow millions to experience live theatre at a reasonable price, but it would also help break the veneer that NYC theatre is for the rich and posh.

The city already generates a gross metropolitan product (GMP) in the trillions; spending a fraction of that on establishing a “Broadway Fund” to make productions affordable would surely boost the city’s morale. And if studies are to go by… in a few years… New Yorkers might seem less prickly and more empathetic.

And while we’re at it, let’s start serving ice cream during intermission too. That alone could probably cover the costs of the subsidies.